History of SAPFA

The South African Power Flying Association is an independent association affiliated to the Aero Club of South Africa formed in the 1980’s.

The Aero Club was formed in 1920 by a group of airman, “Millers Boys”, who had served with the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service. In 1928, due to lack of funds, the club went into recess.

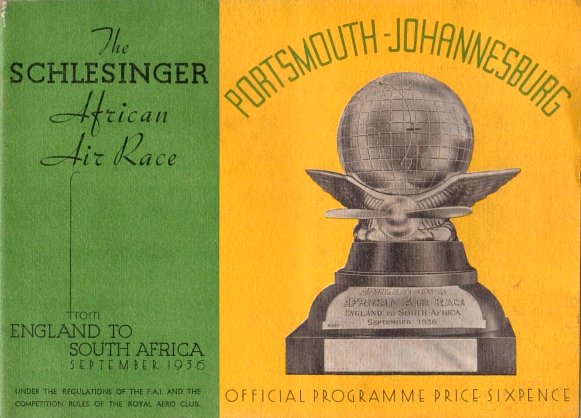

It was revived again in 1936 when Mr I W Schlesinger offered £10.000.00 in prize money for the promotion of an air race from England to Johannesburg. See the 1920’s – London to Cape Town page for further details.

A further £10.000.00 was donated by Sir Abe Bailey to promote Civil Aviation in South Africa, part of which was used for the establishment of a National Controlling Body for Aviation.

In 1939 as World War II hostilities began, Aero Club opened a Civil Pilots register to enable government to readily mobilize those in civil aviation or those with any past flying experience. When war was declared all the established flying clubs were turned into military units with many of these men giving the SAAF a name and reputation unequalled before.

At the end of the war in 1945 the Aero Club set about the re-establishment of clubs throughout South Africa. Initially the Aero Club represented only power flying but as other branches of aviation developed new sections were formed.

Sub committees were formed to run the various sections, the main one still being the Power Flying committee. As other forms of aviation gained popularity the other sections showed rapid growth.

In the late 1980’s the sections of Aero Club were constituted as independent organisations all affiliated to Aero Club and subscribing to the aims and objectives of Aero Club in their particular branch of aviation. The first committees of the independent sections took office in 1988. The sections are:- Power Flying, Gliding, Parachuting, Aerobatics, Ballooning, Hang Gliding & Paragliding, Aero-Modelling, Homebuilders, Microlighting, Experimental Aircraft, Gyro Planes, Virtual Aviation, Rocketry and Disabled Aviators.

Aero Club is affiliated to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale – the world controlling body for sport aviation. No competitive recreational flying activity in South Africa is recognized without Aero Club approval. This includes world record attempts.

Recently, the Aero Club became involved in development programs to expose those previously isolated communities to aviation and liaise such with the Department of Sport and Recreation. The development actions of SAPFA can be found here.

A general committee elected by the members and representing each of the 14 sections, is responsible for the administration and development of the Aero Club’s policies in the interest and well being of sport aviation in South Africa.

Since 1937 Aero Club and SAPFA have been organising the President’s Trophy Air Race (formerly the Governor General’s Cup Air Race). For more information on the history of this event – see Race History